Keyhole Groups Don’t Stop Threats: A Scientific Analysis of Defensive Incapacitation

Keyhole targets—one ragged hole on paper—are a precision flex, not a stopping doctrine.

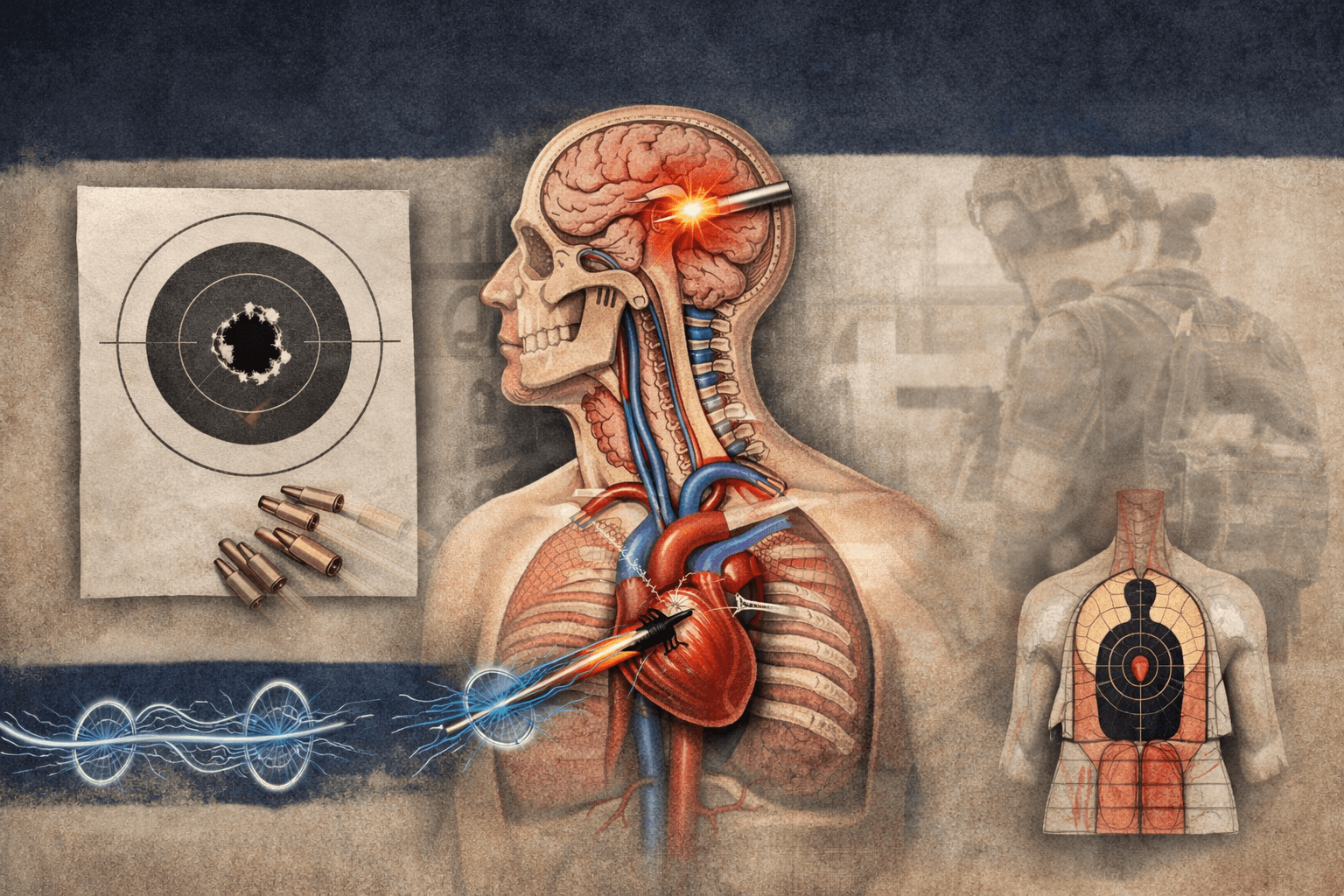

In real-world defense, the priority is rapid threat neutralization, which is driven by physiological system failure:

CNS disruption (“switches”) and circulatory collapse (“valves/pumps”)—not the aesthetics of a group.

Abstract

“Keyhole” target results—tight clusters or a single ragged hole—are widely celebrated as proof of defensive readiness.

This paper analyzes that belief through wound ballistics and human physiology and demonstrates why extreme paper precision is frequently

non-predictive of rapid threat neutralization. Real-world incapacitation is governed primarily by (1)

central nervous system (CNS) disruption (“switches”) and (2) circulatory collapse and loss of cerebral perfusion

(“valves/pumps”). We also review “hydrostatic shock” / ballistic pressure-wave claims and

explain why—especially for handgun velocities—

reliable incapacitation cannot be assumed from energy-transfer narratives. The operational implication is direct:

prioritize time-relevant, anatomically meaningful hits over aesthetic group tightness.

1. Introduction: What “Keyhole” Targets Measure—and What They Don’t

In common range language, a “keyhole” target usually means one of two things:

- One-hole / ragged-hole groups (extreme shot clustering), a measure of repeatability, or

- True bullet keyholing (a tumbling bullet leaving an oblong hole), which is a stability problem and unrelated to marksmanship.

This article addresses the first meaning: stacking rounds into one hole. Shot grouping is a precision diagnostic—useful for confirming

fundamentals under controlled conditions—but it is not a direct surrogate for incapacitation mechanics in living tissue

(Patrick, 1989).

2. The Physiology of Stopping: “Switches and Valves”

2.1 The “Switch”: CNS Disruption

The most immediate and reliable mechanism for rapid incapacitation is physical disruption of the brain or upper spinal cord,

producing an abrupt loss of purposeful motor control

(Patrick, 1989).

This is the true “switch” model: disrupt the critical neural structures and the

system can fail quickly.

2.2 The “Valves/Pumps”: Circulation and Cerebral Perfusion Failure

Most handgun incapacitations occur through hemorrhage and collapse of effective circulation, not “knockdown” effects

(Patrick, 1989).

Threat neutralization ultimately requires the brain to lose oxygen delivery. When cardiac output ceases abruptly, the timeline is not instant:

loss of consciousness can begin around ~8 seconds after the last heartbeat, with circulatory standstill following shortly thereafter

(van Dijk et al., 2020).

Operational reality: even a lethal vascular injury can leave a dangerous window—seconds or longer—where the attacker can still act.

3. Wound Ballistics Fundamentals: What Handguns Reliably Do

3.1 Permanent Cavity Is the Workhorse

Law-enforcement wound ballistics literature consistently emphasizes that handgun effectiveness depends primarily on

penetration and the permanent wound track—tissue crushed, cut, and destroyed along the projectile path

(Patrick, 1989).

3.2 Temporary Cavity Has Limits at Handgun Velocities

Temporary cavity (tissue stretch and displacement) exists, but its ability to cause significant damage depends on projectile velocity and tissue properties.

It is generally more consequential with higher-energy projectiles than typical service handguns

(Fackler, n.d.).

4. Hydrostatic Impact Force and Ballistic Pressure Waves: What Can Be Said Responsibly

“Hydrostatic shock” is often used to claim a pressure wave causes remote damage or rapid incapacitation independent of the wound path.

The literature is debated:

- Some authors argue evidence supports ballistic pressure waves contributing to injury and incapacitation

(Courtney & Courtney, 2008;

Courtney, 2011). - Other perspectives emphasize that direct tissue destruction and penetration are the most dependable mechanisms, and pressure-wave claims are frequently overstated,

particularly for handguns

(Fackler, n.d.).

Defensive conclusion: pressure phenomena may exist, but they are not sufficiently reliable to build a stopping plan around—especially with handgun velocities.

Treat “hydrostatic” narratives as a possible contributor, not your primary mechanism.

5. Why “Keyhole” Grouping Is a Poor Defensive Metric

5.1 Keyhole Shooting Optimizes the Wrong Constraints

One-hole groups are usually produced under controlled conditions: stable stance, predictable cadence, fixed distance, known lighting,

and a non-moving target. Defensive encounters invert those assumptions: movement, angles, time compression, uncertainty, and physiologic stress.

Keyhole practice trains “paper success,” not necessarily time-to-effect physiology—the ability to place rounds into anatomically meaningful zones quickly enough

to shut down the “switch” or collapse the “valves”

(Patrick, 1989).

5.2 Stacking Hits in the Same Micro-Spot Can Be Redundant

If multiple rounds pass through essentially the same narrow channel, the incremental disruption may be small compared with distributing effective hits across

structures that matter: high CNS, upper thoracic vital structures, or targets that degrade mobility and weapon employment.

5.3 The “Single Hole” Mindset Can Slow the Only Thing That Matters: Time

Extreme precision goals often foster over-confirmation and cadence collapse. But circulatory incapacitation is time-dependent

(van Dijk et al., 2020).

The training priority becomes: reliable hits delivered fast enough to create failure of function—not the prettiest hole on cardboard.

6. Applied Examples: Medical Reality, Not Movie Logic

Example A: CNS “Switch”

A hit that disrupts the brainstem or upper spinal cord can produce rapid loss of purposeful movement

(Patrick, 1989).

Training implication: “tiny groups anywhere” is irrelevant unless it maps to switch anatomy.

Example B: Circulatory “Valves and Pump”

Catastrophic injury to the heart or great vessels may cause rapid perfusion loss, but the attacker may remain functional for seconds—sometimes longer—depending on physiology and behavior

(Patrick, 1989;

van Dijk et al., 2020).

7. What to Measure Instead of “One Ragged Hole”

If the mission is lawful, controlled threat stopping, performance metrics should map to real constraints:

- First-shot time + vital-zone hit

- Multiple anatomically relevant hits under time (repeatability, not artistry)

- Hits while moving / from imperfect positions

- Decision-making under stress and post-shot assessment

This aligns training with what wound ballistics and physiology support: penetration, permanent cavity, and system failure pathways—not aesthetic group tightness

(Patrick, 1989;

Fackler, n.d.).

Conclusion

Keyhole groups are a precision diagnostic, not a stopping doctrine. Real-world incapacitation is driven by physiological system failure:

the CNS “switch” and the circulatory “valves/pump”. Handguns are limited tools; their most dependable wounding mechanism is

direct tissue destruction along a sufficiently penetrating path—not guaranteed pressure-wave miracles. Train for

time-relevant, anatomically meaningful hits under realistic constraints, not the illusion that a single ragged hole equals rapid threat neutralization.

References

- Courtney, M., & Courtney, A. (2008). Scientific Evidence for “Hydrostatic Shock”. arXiv:0803.3051.

https://arxiv.org/pdf/0803.3051 - Courtney, M. (2011). History and evidence regarding hydrostatic shock. PubMed.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21150479/ - Fackler, M. L. (n.d.). What’s Wrong with the Wound Ballistics Literature. RKBA.org.

https://www.rkba.org/research/fackler/wrong.html - Patrick, U. W. (1989). Handgun Wounding Factors and Effectiveness. FBI Academy, Firearms Training Unit (Quantico, VA).

PDF - van Dijk, J. G., et al. (2020). Timing of circulatory and neurological events in syncope. Clinical Autonomic Research (via PMC).

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7082775/